Python packaging and community: my first talk at PyCon US 2024

This year I gave my first talk in the PyCon US main track! For context, PyCon US is a big meeting—with over 2,700 registrations this year—a record for the event! My talk was about my experiences navigating the packaging ecosystem from a few perspectives:

- Teaching scientists how to share their code,

- As a maintainer of a smaller Python package—stravalib and

- Founder and Executive Director of a non profit organization - pyOpenSci - which strives to support scientists in tackling the world’s greatest challenges using open software and workflows.

The irony of these three different perspectives is that the challenges that users face in each category are similar! Below I explore my experiences pulling together the talk.

You can also watch the talk here:

My early experiences with Python packaging

I started thinking about Python packaging in 2018 during our early pyOpenSci community meetings. In these meetings, we were trying to create an open peer review process for scientific Python software. A process that is running today with 17 scientific Python packages currently in some state of review as write this post.

As someone who was teaching Python to beginners and dabbling in creating and maintaining packages to support teaching, packaging was this somewhat undefined space. I wasn’t sure where to begin or what sources were truly authoritative. Generally, my approach to packaging was copying the infrastructure that other package maintainers I trusted used—mainly GeoPandas.

I am a spatial data nerd at heart.

But as I thought about creating pyOpenSci’s open peer review process, I knew scientists would need a process that:

- Enforced “good enough” practices in scientific Python packaging

- Was not overly-binding, but also set users up for success

I also knew that:

- We needed to create some sort of packaging guide that set up expectations for our pyOpenSci open peer review of software process, and that

- I wasn’t the lead expert in the room. Thus, we needed people from across the (scientific) Python ecosystem and beyond to build consensus and define what were “good enough” practices.

But how could pyOpenSci in these early years, as a not-yet-created community, empower people to navigate a tricky, if not complex, ecosystem empowered by choice?

Choice is a value in the Python ecosystem

In the Python ecosystem, choice is a value.

Why?

Because the Python language is used across many different domains and for lots of different reasons. And further, Python is a “glue” language. This means that it can wrap around other languages like C—making it even more flexible.

This flexibility warrants choice. It’s almost by design.

And I value choice too.

Too much of a good thing? Too many choices?

Choice is great but it’s not necessarily beginner friendly. Choice leaves too much room for uncertainty as a beginner. And uncertainty just makes learning more stressful.

As my mentor and colleague Carol likes to say:

choice is an opportunity for someone to make the wrong decision

So if you think about that “opportunity to make a wrong decision”, imagine what happens if you have multiple choices that lead you down a terrifying path of uncertainty!

The evolution of the pyOpenSci Python packaging guide

Years later, what started out as a generic Python development guide, was transformed into what’s now the pyOpenSci Python package guide.

- A guidebook that has 58 contributors as I’m writing this post today.

- A guidebook that has color and graphics and that leads Pythonistas down a singular, opinionated path to Python packaging success.

- A guidebook that breaks down pieces and processes into their fundamentals and explains them using digestible words.

The pyOpenSci path is not the only path. It is just a path that works and enables early wins for scientists and others using Python.

If you’re reading this and you have your own path, that’s OK too. But if you want to worry less about decisions and have a definitive way of doing things that follows modern standards -

we’ve got you.

A packaging guidebook created by community

This guidebook was created by a community of people with beginner to expert packaging experience with the goal of building consensus around a single approach to pure Python packaging that would yield user success.

Together we created a guidebook that acknowledges a suite of fantastic tools across the ecosystem, while still leading users down a streamlined path.

Getting accepted to talk about packaging…

I was thrilled and terrified to be accepted to give a talk at PyCon US, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on the process of creating the pyOpenSci Python packaging guidebook . My talk was called:

“Friends don’t let friends package alone”

It was all about the process of navigating the Python packaging ecosystem and then creating the guide. While you might assume such a talk about be technical, in reality, it was all about people.

Me and the child-like imposter inside

Giving this talk was a big deal for me. Imposter syndrome—the feeling that I didn’t belong, that I wasn’t technical enough to build pyOpenSci—has always been my reality. As a trained Landscape Architect, I spent most of my college and early graduate years practicing perfect lettering, using markers, fancy pens and colored pencils to bring creative landscape visions to life. I think moved on to get an advanced degree in ecology.

I remember vividly almost crying when I tried to read and understand my first scientific paper.

…talk about jargon and technical terms!

Now, I consider myself a Pythonista, coder, data scientist, and tech geek. I’ve bounced around across different data science languages.

AND, I’m very aware of how much more others know than I do about lots of different topics—including packaging.

I wasn’t sure what it would be like to be on that big pyCon US presentation stage, in that big room full of chairs. Would they be empty? Luckily, I was able to focus on my friends sitting in the front rows.

Carol, Hugo, Jeremiah, and Inessa—they were all there.

Carol told me to lean into the teacher inside of me. I know that teacher best. My body calmed as I remembered why I was there. To help the community move forward.

And similar to how we created our packaging guide—my friends got me through it.

The core messages in my talk

In my talk, I shared my experiences as a maintainer of stravalib. How challenging it was to figure out the best packaging infrastructure for our team. However, that experience of rebuilding stravalib also empowered me to better understand the pain points in the ecosystem from a “beginner and real world application lens.” From a lens of “I just need to create a package and publish / release it to PyPI regularly.”

From a lens of—I am technical but I need to learn new-to-me packaging tools and workflows.

Fundamental first—How to make a technical ecosystem beginner accessible

How do we collectively support and empower people who don’t want to become packaging gurus to be successful?

My approach to helping beginners tackle hard technical problems has always been about breaking things down into their simplest forms first.

I thrive on those “ah ha” moments when a tough concept clicks.

And someone gets it.

Sometimes, that someone is me — before I can teach the topic to others!

So what about packaging with friends?

The essence of my Python packaging talk was the work that I have lead alongside the pyOpenSci community to demystify and help people navigate the complex Python packaging ecosystem.

This work was really about people helping people tackle challenging things.

Python packaging matters because scientists need open software to create open and reproducible workflows to build upon each other’s work, and to tackle the world’s hardest challenges more efficiently and effectively.

Among other things, pyOpenSci reviews software as a constructive way to help scientists both create better software and get credit for the important work they are doing.

The pyOpenSci community has created a Python package guide that harnesses the expertise, opinions, and experiences of 61+ people.

This guide provides:

- A beginner-friendly overview of the packaging ecosystem combined with a

- Start-to-finish tutorial that uses Hatch to create a Python package.

Python is known for its incredible community, so it only made sense to leverage that collective knowledge and experience to create a packaging guide. Packaging doesn’t have to be complex. Friends can help.

The talk can be broken down into 4 takeaways:

People can help (surprise!)

When tackling some of the most thorny technical Python problems, people can help. This might mean:

- Learning together by working in a small supportive group to create your first Python package;

- Bringing in experts to review and vet online resources to ensure they are accurate and accessible that support scientists worldwide in their packaging journey.

- Also including beginners to ensure the content is accessible, understandable and usable.

- Running a constructive peer review process where people volunteer their time to provide feedback on a package’s usability, function, and structure.

In creating the guide, we knew we were tackling hard, complex technical problems. But also there is a tremendous amount of collective knowledge in this community that can be harnessed and focused on the problem at hand. By focusing people on the users of the guide first, rather than tools, we were able to build consensus.

We were able to move forward together.

Create early wins for users

As an educator, I’ve always known that the best way to empower someone new to any topic is to create a learning environment where they quickly make progress. I’ve collected data on what approaches work better than others. I’ve explored how certain presentations of information empower, while others break people down, triggering imposter syndrome and even isolation within a science field.

The key is early wins.

Early wins empower users to:

- Want to do more

- Feel like they belong and can be successful learning the skill at hand

- Try again and expand their knowledge

- Even help their colleagues, which is the biggest win of all.

High quality documentation (or tutorials) helps users achieve this by providing quickstarts and resources that ensure they can get up and running quickly and have early positive experiences.

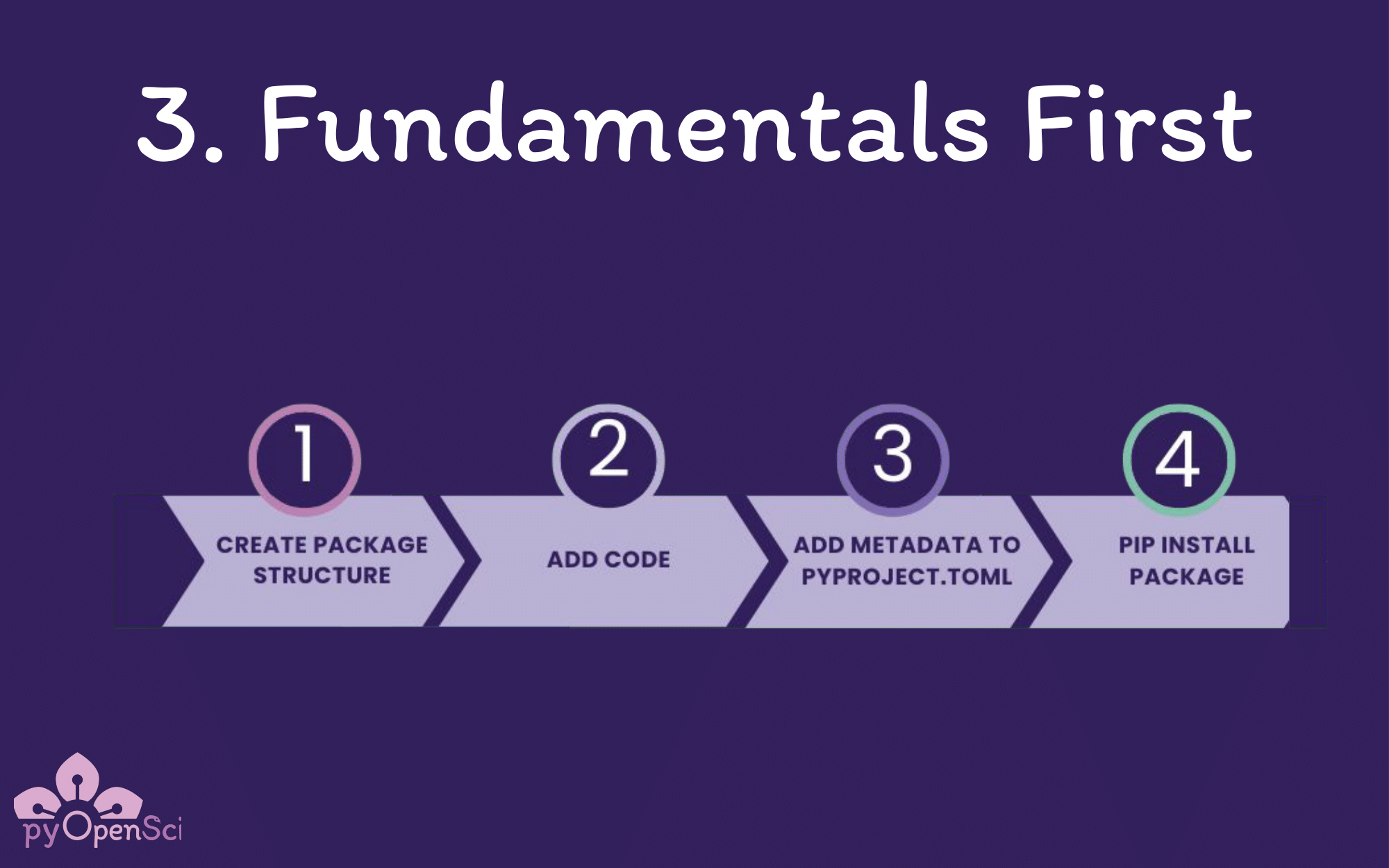

Fundamentals First

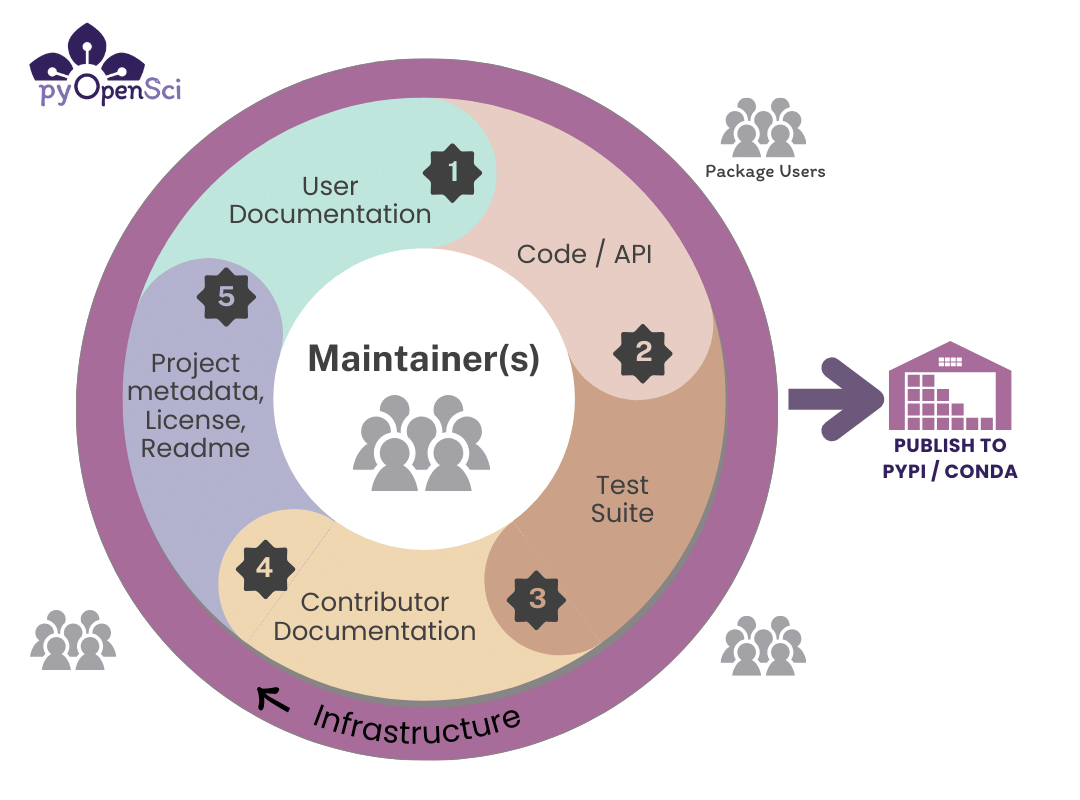

When teaching beginners, break things down to their fundamental concepts. In the case of packaging, this means explaining pure Python packaging in its most basic form, without immediately discussing tools. Notice that the diagram below doesn’t discuss tools at all!

While some may think that this approach is over simplified, it’s not. The idea here is that you begin with digestible information that empowers a learner. You help them understand that they can do this! And then, and only then, you add more complexity when they are ready to absorb it.

This also opens the door wide to early wins.

Just say no to TMO

Avoid TMO—Too Many Options or Too Many Opinions at all costs when teaching beginners. Options are great, but when someone is new to a topic, it’s best to give them a straightforward path to success.

Early on in creating our packaging guide, we found contributors, often quite expert in the packaging ecosystem, arguing about the best tools and best practices. Since we invited many people with different levels of experience to review our content, these arguments pushed some people away and created an unhealthy environment. Moderating these conversations to focus on the users and their needs, rather than debating tools, was critical. This approach helped create a truly beginner-friendly guide and fostered a review environment that was safe and inclusive, where both beginners and experts could contribute.

Friends don’t let friends package alone

When I finished my talk, I felt this sense of relief but also I felt love, support and deep passion for this topic and the community. It’s more than just packaging. It is about empowering people with skills that will help them tackle the biggest scientific challenges that we face as humans. Science is about data. And to process data we need tools - open tools that are accessible for scientists to learn and use. It’s about carving out space for scientists to build and use these tools. And also to make space for people who may feel like outsiders, because of who they are, to participate.

I’m excited to have the privilege of moving the pyOpenSci mission forward, and of getting to connect with so many amazing people. I’m excited to continue to facilitate and support better science through better software and to empower more people with skills. And maybe, through this talk, a little piece of that child-like imposter within me has been chipped away!

I’m human too. I need friends too.

Connect with us!

There are many ways to get involved if you’re interested!

- If you read through our lessons and want to suggest changes, open an issue in our lessons repository here

- Volunteer to be a reviewer for pyOpenSci’s software review process

- Submit a Python package to pyOpenSci for peer review

- Donate to pyOpenSci to support scholarships for future training events and the development of new learning content.

- Check out our volunteer page for other ways to get involved.

You can also:

- Keep an eye on our events page for upcoming training events.

Follow us on social platforms:

If you are on LinkedIn, check out and subscribe to our newsletter.

You can also:

- Check out our Python Package Guide for comprehensive packaging guidance

- Keep an eye on our events page for upcoming training events

Leave a comment