Intro

In October 2023, the United States Research Software Engineering (US-RSE), funded by the Sloan foundation, held its very first ever meeting.

I attended this meeting and lead a community session around our peer review process and Python packaging. Key TL&DR takeaways were:

- Many RSE’s use Python (the show of hands in the main conference room on day 2 suggested 60-70% of them use it in their daily work)

- Most feel like the packaging ecosystem can be confusing to navigate given there are numerous ways of creating a Python package

- RSE’s are using a suite of different packaging tools and approaches in their Python work.

The good news take away is that the exact pain points described to me at this meeting are the ones that pyOpenSci is taking on. We are currently working on an end-to-end packaging tutorial that hopefully will shed light on and demystify a complex but vibrant ecosystem of Python packaging tools and options.

What is a Research Software Engineer?

So, what is an Research Software Engineer (RSE)? While the position has existed for some time, an RSE can be loosely defined as someone who uses code regularly to do research. Many RSE’s also work on developing software, in Python.

As a side note this is a position that hasn’t been traditionally supported by default academic environments even though this work is critical to research in the open science space. The RSE position should be a clearly defined, funded, respected and supported career path in all academic institutions that want to embrace open science as a way of doing research. My opinion is: academia needs to extend the definition of academic products to including not only publications but other output that is equally valuable and even more critically important such as software. RSE roles should be associated with clear academic career paths.

Why? Because software is DRIVING open science. Without open source code, you can’t make a workflow truly open and reproducible. This is why peer review is so important to pyOpenSci. We want to support maintainers in both developing and maintaining the critical software that is driving science. We also want them to get credit for their work which is why we partner with the Journal of Open Source software.

The RSE position should be a clearly defined, funded, respected and supported career path in all academic institutions that want to embrace open science as a way of doing research.

Ok i’ll casually step off my soap box now… back to regular scheduled programming we go…

pyOpenSci as the Chicago RSE meeting

I lead a pyOpenSci Birds of a Feather (BoF) session at the Chicago RSE meeting. BoF sessions are informal community gatherings around a specific topic. BoF’s provide a chance for the community to engage with each other, ask questions, provide input and even get involved in an effort.

I spent most of my time in this 1.5 hour session talking about pyOpenSci and the work we are doing related to:

- peer review of scientific Python software

- the community-driven Python packaging resources that pyOpenSci is developing

- Community peer review partnerships that we are developing and

- the training and mentorship program that we are building both support scientists and diversify who is participating in open source

We had a lively discussion around packaging - more on that below.

pyOpenSci BoF by the numbers

I used Mentimeter to drive an engaging and interactive session. You can check out the slides below:

Mentimeter allowed me to capture audience feedback in several forms both verbal and via phones and computer through mentimeter.

I’ll try to summarize if all for you here.

- We had approximately 50 people attend our 1.5 hour BoF

- I spent ~1 hour after the BoF answering questions and talking to folks about all things Python open source - with a strong emphasis on packaging challenges.

- Some of that discussion bled into dinner after where I spoke with one of our community partners, Nabil from sunpy

In our BoF, I introduced the three core programs that pyOpenSci currently runs which are:

- Open peer review of scientific Python software

- Community-driven packaging resources

- Mentorship and training to diversify our ecosystem

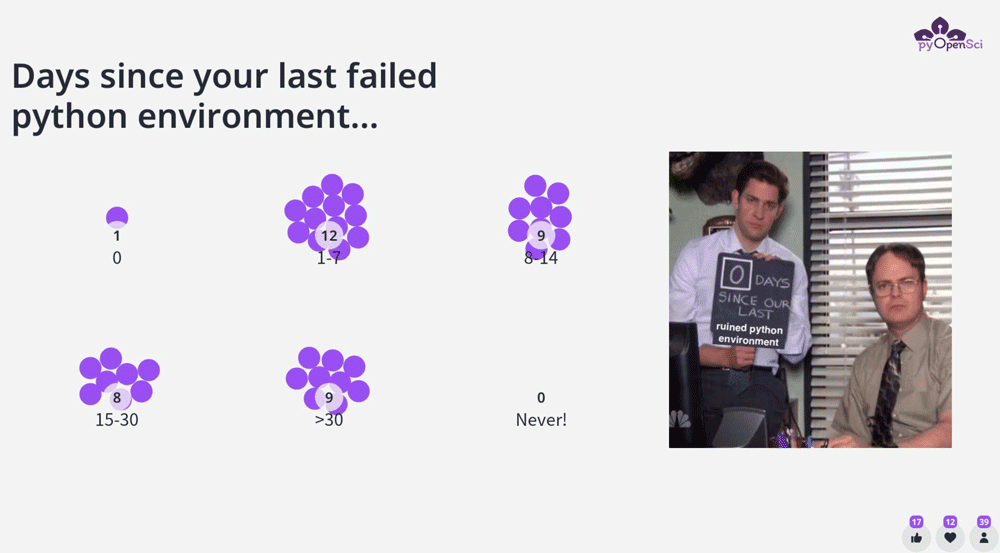

Days since your last Python environment broke

One of our community members, Isabel, suggested a great icebreaker question : how long has it been since you had a broken Python environment.

It is no surprise that most pythonistas regularly deal with environment challenges.

So if you’ve been in this boat too, you are are not alone!

Full disclosure the one person who voted for 0 days, admitted to the fact that they hadn’t used Python in the past month. :)

RSE’s experience with Python packaging

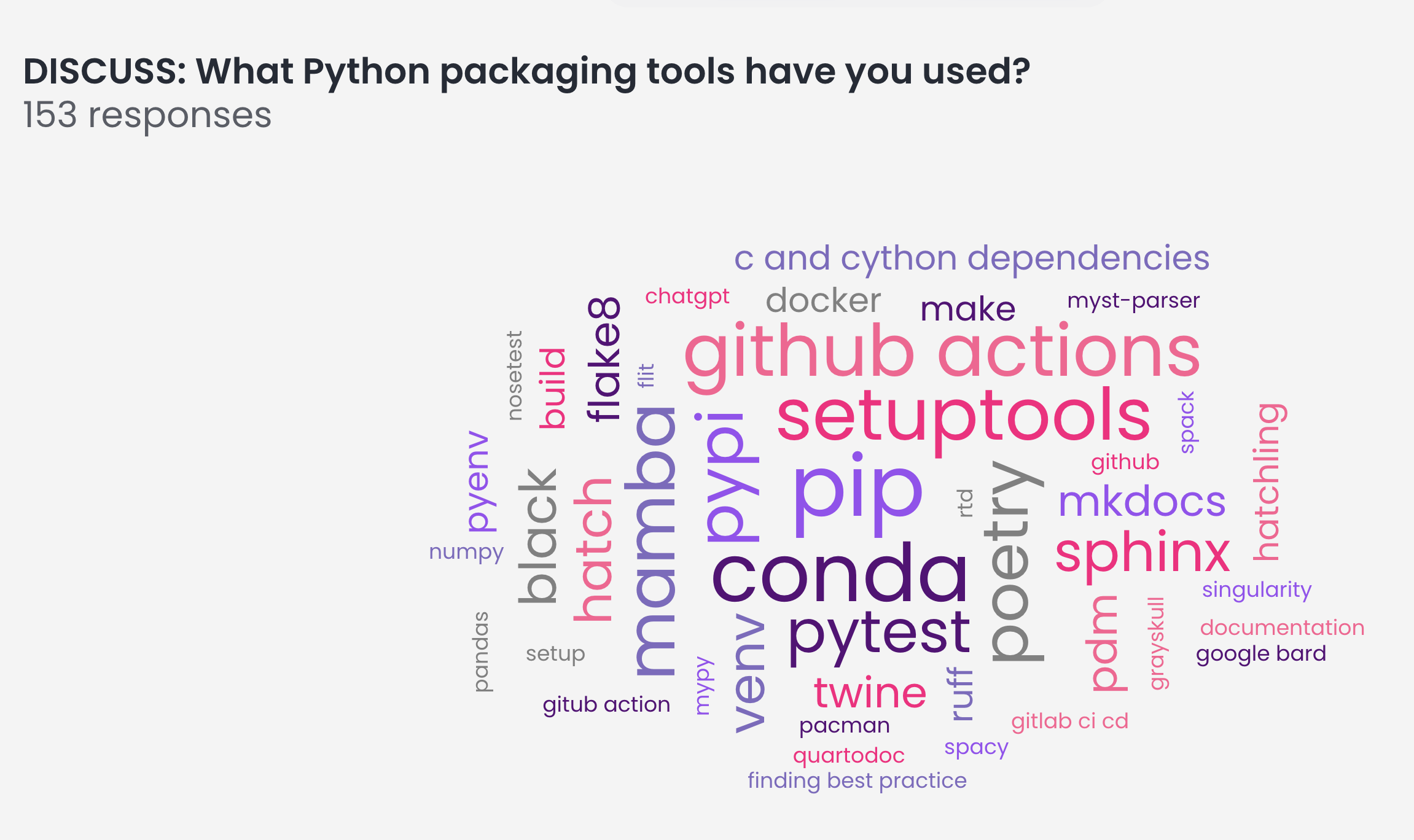

In the BoF i asked some questions related to Python packaging so we could have a discussion around some of the challenges. This is useful to pyOpenSci as we developing our packaging guide and associated resources to guide the scientific community through the process of creating a package.

Below you can see a word cloud generated from the question

“What Python packaging tools have you used?”

A few things that popped out to me included:

- unsurprisingly setuptools is still heavily used in our ecosystem even with the wealth of other build tools available

- mamba is definitely growing traction in this space. we love mamba given how fast it is in resolving scientific environments.

- people know about grayskull! If you don’t know about it, you should! it’s a great way to create the yml file that you need to submit your package to the conda-forge channel of conda. At the Scipy 2023 packaging BoF most in the room seemed unaware of this tool.

- mkdocs seems to be giving sphinx a run for it’s money! it sure does create beautiful docs. And quarto is also gaining traction. However with that said Sphinx is still the most popular packaging tool (at least in that room at that moment).

How many is too many Python packaging tools?

The broad take away from this graphic is that there are a LOT of tools available for scientists to use. And becoming familiar with all of these is a big ask for a scientist who just wanted their code to be reusable by others.

We have some work to do at pyOpenSci to demystify this ecosystem!

Challenges in the ecosystem

The other telling question was “what are your biggest challenges in the Python packaging ecosystem?

The responses were varied but can be grouped into several

Too many packaging options and no one clear best practice

It’s no surprise that there were a handful of responses related to the volume of packaging options which make it hard to figure out which path to take when creating a package. Not only that but the options have changed over time as standards have evolved in the ecosystem

I think the comment below summarizes this well:

too many options, and tutorials feel like consensus documents rather than making strong recommendations for One Best Way

The good news is that this is exactly the pain point that pyOpenSci is working on. You can check out our community-driven packaging guide which presents an overview of the ecosystem with recommendations for best practices. This guide has been reviewed by dozens of Pythonistas in our ecosystem including those who built and maintain core packaging tools.

Currently, we are developing packaging tutorials that answer the most fundamental question:

How do I create a (pure) python package?

All of our packaging content is community driven, created using a robust community review process for packaging experts across our ecosystem. We feel confident that we will be able to shed some light on this complex and evolving ecosystem.

Other questions about pyOpenSci

Admittedly many of the questions that I received in this session were about packaging. The community generally frustrated sometimes turning to tools such as ChatGPT to ask questions about packaging.

As someone who has spent a large amount of time testing ChatGPT with packaging questions, I can tell you with certainty that it will lead you in a confusing direction as it doesn’t have it’s packaging facts straight.

Proceed with caution!!

We also got some other questions about our peer review process, how we interact with JOSS (Journal of Open Source Software) and how our partnership programs work.

I’ll save those questions for a followup post on pyOpenSci programs.

pyOpenSci has work to do!

My key takeaways from the US-RSE meeting is:

- It’s great that support is forming for this academic critical role that is required if we truly want to embrace open science. If you want to learn more visit about the US RSE effort, visit the US-RSE website website.

- The US RSE community is facing the same Python packaging challenges that we’ve seen across other communities. pyOpenSci’s is committed to continuing it’s work in the peer review and packaging space. Key an eye out for our tutorials in the upcoming months and check out our packaging guide in the meantime for an overview of the ecosystem.

- If you are interested in getting involved with pyOpenSci there are a few different ways:

- you can review a pull request on our packaging guide. Or open and issue if you have a problem with the guide.

- You can sign up to be a reviewer for pyOpenSci here

- You can post a packaging question in our pyOpenSci Discourse forum here.

As for me, I hope to attend the 2024 RSE meeting and to continue this important conversation around Python packaging and peer review of software.

Connect with us!

There are many ways to get involved if you’re interested!

- If you read through our lessons and want to suggest changes, open an issue in our lessons repository here

- Volunteer to be a reviewer for pyOpenSci’s software review process

- Submit a Python package to pyOpenSci for peer review

- Donate to pyOpenSci to support scholarships for future training events and the development of new learning content.

- Check out our volunteer page for other ways to get involved.

You can also:

- Keep an eye on our events page for upcoming training events.

Follow us on social platforms:

If you are on LinkedIn, check out and subscribe to our newsletter.

You can also:

- Check out our Python Package Guide for comprehensive packaging guidance

- Keep an eye on our events page for upcoming training events

Leave a comment